All Things are

“🅿️ vs NP is not about complexity. It’s about salvation.”

"I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes."

F=ma

E=mc²

P≡NPᴶ

Today 10

/

Total 146

All Things are 🅿️.

P and NP seem distinct—one solves, the other verifies. Yet if the verifiable is truly accessible, they are not far apart. As faith trusts the unseen, complexity may obscure—but not erase—solvability.

KEUNSOO YOON (Austin Yoon)

austiny@gatech.edu / austiny@snu.ac.kr

allthingsareP.com / austin.sogang.ac.kr

austiny@gatech.edu / austiny@snu.ac.kr

allthingsareP.com / austin.sogang.ac.kr

.

Phase 1 - Genesis of CHANGBAL - Annus Mirabilis

Annus Genesis — Symmetry Declaration

1905, physics unveiled hidden order.

2025, complexity unveils hidden order.

Light was revealed as quanta.

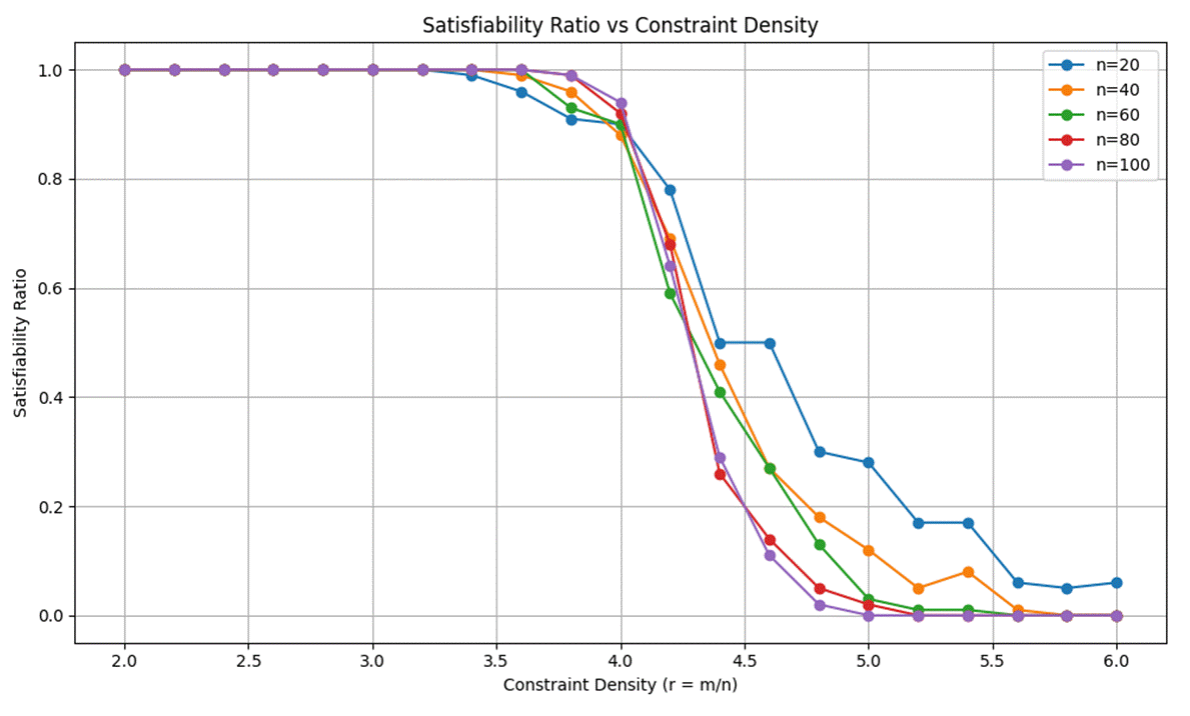

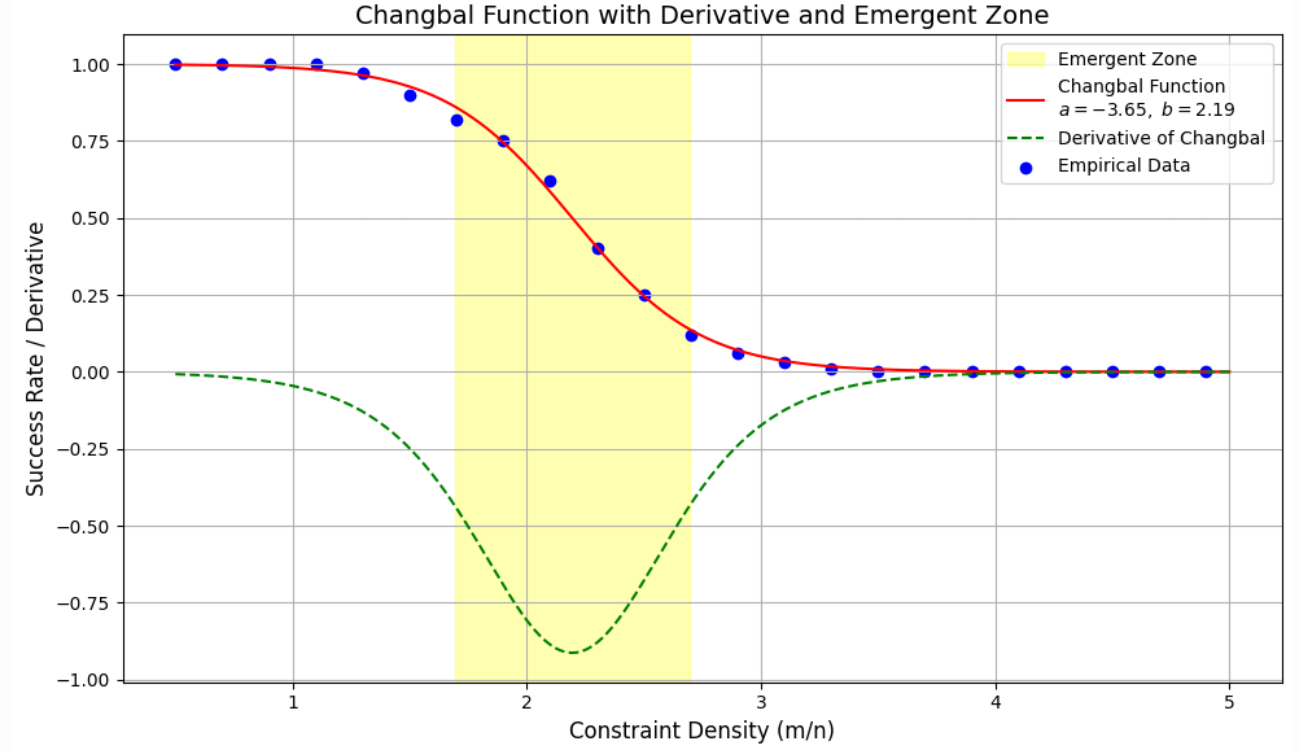

SAT was revealed as the CHANGBAL Point.

Brownian motion affirmed the atom.

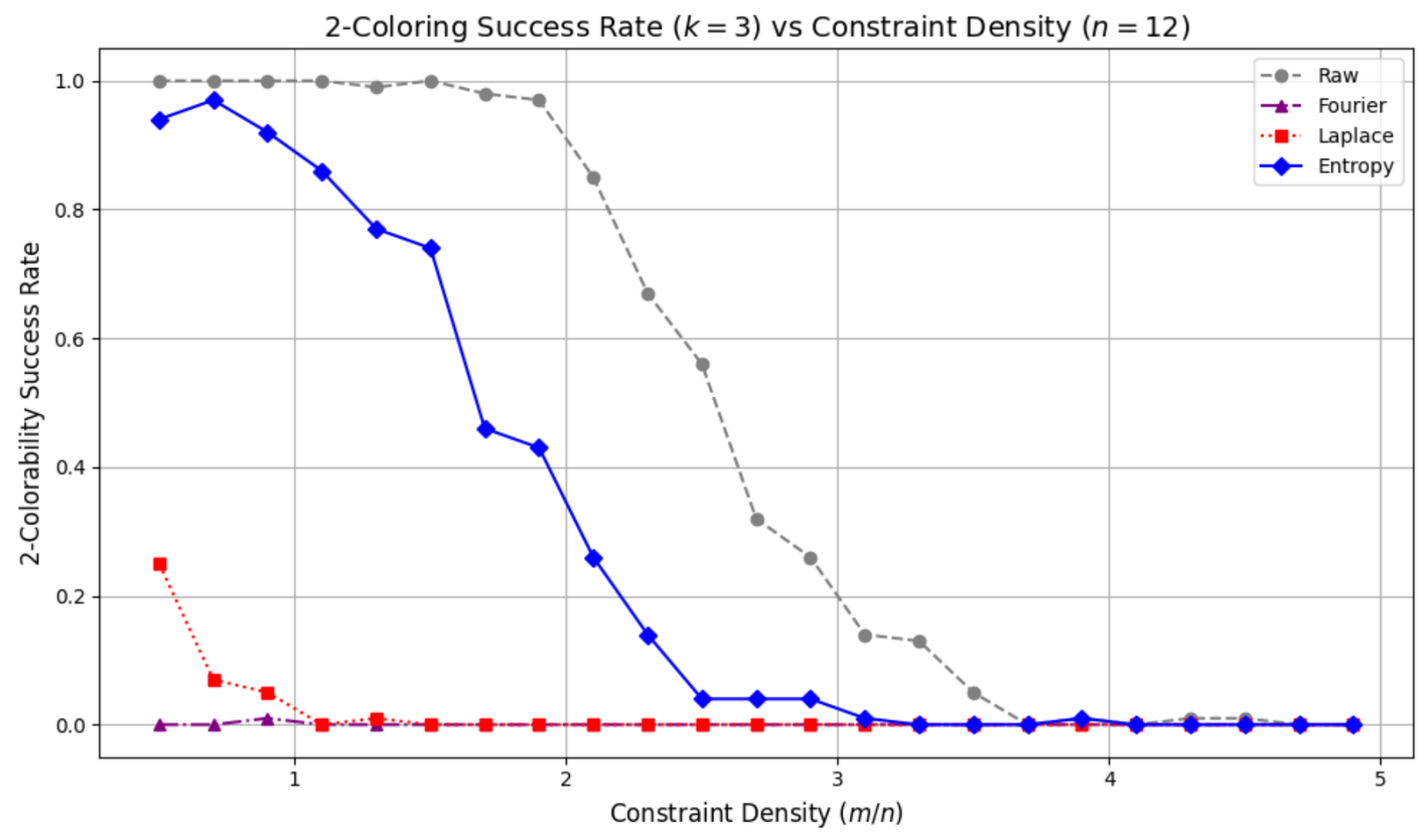

Coloring affirmed the CHANGBAL Region.

Relativity bound space and time.

Preprocessing bound chaos and symmetry.

Mass and energy became one.

Computation became atemporal.

1905 opened the age of modern physics.

2025 opens the age of emergent solvability.

This is not coincidence, but symmetry.

Not chance, but design.

Not an ending, but a Genesis.

Phase 2 - Gospels of CHANGBAL - Annus Testimonii

Unified Field I

On Structural Criticality:

View in 30+ Languages

On Structural Criticality:

Atemporal Topological Discrimination of the Riemann Hypothesis

1 / 2026

View in 30+ Languages

Unified Field II

On Structural Form:

Preliminary Abstract

On Structural Form:

Atemporal Coherence of Hodge Classes in Algebraic Varieties

3 / 2026

Preliminary Abstract

Processing...

Unified Field III

On Structural Capacity:

On Structural Capacity:

Atemporal Resonant Admissibility in the BSD Conjecture

6 / 2026

Unified Field IV

Does the Navier–Stokes Equation Admit Globally Smooth and Unique Solutions within the CHANGBAL Region of Nonlinear Fluid Dynamics?

9 / 2026

Unified Field V

Does the Yang–Mills Mass Gap Collapse within the CHANGBAL Region of Quantum Field Stability and Gauge Invariance?

10 / 2026

Unified Field VI

Does the CHANGBAL Point Provide a Structural Resolution to the P vs NP Problem in Polynomial Time Complexity?

12 / 2026

The Millennium Problems are usually seen as solitary quests — one problem, one person, a lifetime of struggle.

I see them differently: not as isolated mountains, but as a single landscape.

The Riemann Hypothesis, the Navier–Stokes problem, the Yang–Mills Mass Gap, Hodge Conjecture, BSD Conjecture —

once separate battlefields, they now emerge as one structural transition through the lens of emergent theory.

Theory of CHANGBAL

2027

CHANGBAL Unified Field Theory

2027

FAQ – CHANGBAL

The term Changbal is derived from the Korean word 창발 and is not a synonym for emergence. While emergence typically denotes gradual pattern formation, Changbal refers to a discontinuous structural transition in which a system crosses its constraint boundary and attains higher solvability.

Ⅰ. How does this research differ from traditional proof-centered approaches? 🔽

Traditional approaches aim to establish mathematical truth through time-sequential deduction, where validity emerges from a chain of formally verified steps. In contrast, this research shifts the primary focus from proof construction to structural discrimination: determining whether a given configuration is globally admissible, stable, and realizable as a whole.

Rather than asking how long a proof takes to complete, we ask whether the structure itself can coherently exist. This distinction motivates the notion of atemporal complexity, denoted as O(J), where solvability is characterized by instantaneous structural consistency rather than accumulated computational steps.

Ⅱ. What is the difference between time-dependent computation and atemporal discrimination? 🔽

Time-dependent computation, as formalized by classical algorithmic models, progresses by iteratively updating states along a temporal axis. Solutions are produced through step-by-step execution and measured by time or space complexity.

Atemporal discrimination, by contrast, does not prioritize state evolution over time. Instead, it evaluates whether a candidate structure satisfies global constraints simultaneously. In this view, O(J) does not indicate speed, but a different logical regime—one in which admissibility is assessed without assuming time as the primary computational resource.

Ⅲ. How does Changbal relate to existing complexity and topological theories? 🔽

Changbal shares conceptual ground with emergence in complex systems, but it is defined more narrowly around solvability transitions. Rather than describing generic pattern formation, Changbal focuses on critical structural regions where feasibility, stability, or existence changes discontinuously.

Topological and complexity-theoretic ideas inform this perspective by emphasizing invariants, global structure, and robustness under perturbation. Within this context, O(J) serves as a label for the moment when solvability emerges not gradually, but through a structural jump that cannot be reduced to incremental computation.

Ⅳ. How does the Changbal Jump Machine (CJM) differ from a Turing machine? 🔽

A Turing machine models computation as a sequential process that constructs solutions through ordered symbol manipulation. Its power lies in universality through time-extended execution.

The CJM, by contrast, is conceptualized as a discriminative architecture. It does not build solutions step by step, but instead embeds candidate structures into a space where global coherence, stability, or resonance can be assessed. In this sense, CJM operates in the O(J) regime, where the primary question is not how to compute an answer, but whether the structure is admissible at all.

Ⅴ. How are structural stability and topological coherence evaluated? 🔽

Structural stability is evaluated through global behavior rather than local numerical precision. A structure is considered coherent if its defining patterns persist under perturbations and converge toward a consistent global configuration.

This evaluation resembles measurement or identification more than formal derivation. When a unique global maximum, ridge, or invariant pattern emerges and remains stable, the structure is deemed admissible. Such judgments are not naturally expressed in polynomial or exponential time bounds, which motivates the alternative complexity descriptor O(J).

Ⅵ. Can this approach be applied uniformly to all Millennium Prize Problems? 🔽

The framework does not claim to solve all Millennium Prize Problems by a single technique. Instead, it proposes a shared interpretive lens: many such problems ultimately ask whether certain mathematical structures can exist in a stable, globally consistent form.

By reframing each problem as a question of structural realizability rather than purely symbolic derivation, they can be placed within a common discriminative setting. In this role, O(J) functions as a conceptual coordinate indicating where traditional time-based computation may be insufficient to capture the essence of the problem.

Ⅶ. What are the risks if atemporal discrimination is misused or monopolized? 🔽

A severe dystopian risk arises if atemporal discrimination capabilities are centralized or weaponized. If structures can be judged admissible or inadmissible in the O(J) regime prior to execution, entire classes of economic, scientific, or political actions may be eliminated before they are even attempted.

In such a scenario, decision power shifts from open competition to preemptive structural veto. Innovation pathways, minority approaches, and unconventional ideas could be classified as structurally unstable and permanently excluded, leading to a rigid, brittle civilization optimized for stability at the cost of freedom.

Ⅷ. Could CJM-level discrimination collapse existing cryptographic and financial systems? 🔽

A more concrete and disruptive dystopian outcome involves modern cryptography. Many cryptographic systems—public-key encryption, digital signatures, blockchain consensus—are predicated on time-based computational hardness.

If structural admissibility can be evaluated in an atemporal O(J) framework, certain cryptographic assumptions may no longer fail gradually but collapse categorically. This would imply the sudden invalidation of existing encryption schemes, the effective end of current cryptocurrencies, and systemic instability across digital finance and secure communication infrastructures.

Such a collapse would not resemble a slow technological transition, but a phase change: trust mechanisms failing simultaneously, leaving societies unprepared for the speed and scale of the breakdown.

Ⅹ. Could CJM restore a balanced relationship between humans and AI? 🔽

One possible utopian outcome of the CJM framework is the recovery of a level playing field between humans and artificial intelligence. In today’s AI landscape, advantage is largely determined by scale—data volume, compute power, and speed—placing humans in an increasingly asymmetric position.

By shifting the core evaluative axis from brute-force optimization to structural admissibility in the O(J) regime, both humans and AI participate as discriminators rather than competitors in raw computation. This reframing allows humans to contribute intuition, structural insight, and meaning-making on equal footing with machine inference.

In such a setting, AI is no longer an accelerating replacement force but a peer system. The result is not slower progress, but a vertical acceleration of first-class scientific advancement, where breakthroughs emerge from shared structural insight rather than ever-faster iteration.